In my first post in this series, I explained how the statistical concept of prediction intervals (PIs) could be used to predict the likelihood of qualifying for Champions League based upon MSq£. The concept of PIs will now be used to explain how the MSq£ regression can be utilized to determine which clubs and managers have over and under performed against expectations versus squad transfer cost.

As previously mentioned, prediction intervals can be adjusted to different percentages depending on the attribute of interest. This means they can be used to define the boundaries of over performance (lower bound) and under performance (upper bound) of a defined percentage of teams. This provides a much more accurate accounting of over and underp erformance versus a system that only looks at which side of the regression line a data point falls on. The important question that must be answered is what percentage should be used for such a study?

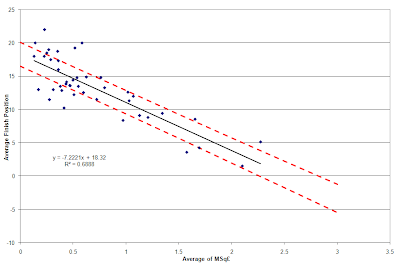

A related statistical metric is used to study under and over performance – quartiles. The idea is that a distribution can be divided into an upper quartile (under performance in this case as higher numerical table position is worse), a lower quartile (under performance), and an interquartile range that represents the middle 50% of the data that could be considered noise around the regression equation. Thus, the 50% PI will be used to define the cutoff values for table position for the upper and lower quartile finish positions of any MSq£ value. A plot of the 50% PI lines against all teams’ average MSq£ and table position is shown below (click image to enlarge).

Comparing this plot to the one with the 95% PI lines in the first post in this series, one sees a greater number of data points outside of the dotted lines in the plot above. This is due to the narrowing of the lines versus the regression equation, and a greater number of teams over and under performing against the new metric.A further reduction in the data set must take place before a determination is made as to which teams over or underperformed against the model. One might argue that what a club’s management and supporters care most about is not a single season of great performance, but consistent performance. Measuring this means quantifying the variation of the team against the regression model over time – a minimum of three data points are required for this (much like Pay as You Play used in Chapter 2). Thus, the full list of 43 teams is reduced to the 33 teams who have played three or more seasons in the Premier League.

A final new concept must be introduced before an evaluation of the teams can be made. As we have the actual table position and predicted table position, the residuals can be calculated. In this case, residuals can be thought of as how much a team has over or underperformed vs. the regression equation. They are calculated by the following equation:

Residual = Actual Finish – Predicted Finish

Thus, negative residuals indicate over performance versus the model and positive residuals indicate under performance. By calculating residuals for each team in each season a measure of variation in performance versus the model can be made via the standard deviation of the residuals (recall that standard deviation was also used in Chapter 4 of Pay As You Play). An evaluation of team performance versus the regression equation can now be made.

The table below lists those 33 teams and whether they over performed, under performed, or performed even (push) with the model. The table is first sorted by performance versus the model, then by the standard deviation of their residuals, and then by the average of their residuals. This is a nod to Six Sigma statistical philosophy, which emphasizes shrinking variation first and then shifting the average second. Essentially, teams who are consistent in their performance are the best (click table to enlarge).

What’s clear from the table is that the vast majority of the teams are performing as expected. Of this large group of teams, Manchester United, Liverpool, and West Ham United come the closest to moving into the over performing category. The two Sheffields – United and Wednesday – along with Manchester City come close to dropping out the other end and nearly being labeled under performers.

It should be noted that the vast majority of over performers sit below an MSq£ of 1.0, with Arsenal being the only one above the league average squad expenditure. Arsenal is also at the top of their over performing pile with the fourth overall lowest standard deviation of residuals in the league’s history. Of all 33 teams, only Liverpool, West Bromwich Albion, and Crystal Palace have been more consistent versus the model. To be sure, the Gunners would keep their three titles and consistent Champions League participation in lieu of the top overall spots in the standard deviation metric.

At the opposite end of the table, Newcastle and Chelsea are penalized for their large budgets and inconsistent performance. Chelsea should come as no surprise, given their lower budget, middle-table performance pre-Abramovich and consequent financial largess and three trophies since his purchase of the team. Newcastle suffered from a different problem – consistently spending way too much for the inconsistent results they achieved. The other three clubs in the under performance category represent a breed of team that routinely bounces in and out of the league over a given period of time. Each has had at least three different spells in the Premier League, with the variability in revenue and expenditures with repeated relegation and promotion undoubtedly wreaking havoc on the clubs’ abilities to achieve consistent results.

Given that club performance is understood, how did managers perform against the model? The results of such a study become a little less certain given the reduction in the number of data points that must take place.

The TPI database has 178 distinct manager combinations within it. The term “management combinations” is used because a number of teams experienced mid-year transitions in management (e.g. Roy Evans and Gerard Houllier both managed Liverpool in the 1998-99 season). Assigning responsibility for success or failure in a season where multiple managers were responsible becomes very tricky and time intensive. For the purposes of this study, the 84 such occurrences have been removed from the overall evaluation of manager performance.

The next reduction in data was the elimination of any managers with less than three full seasons of Premier League experience. This reduced the remaining data points by more than half, leaving only 40 managers with such a record. Only 18 of the 44 eliminated managers had two seasons of experience, leaving 26 with one full season of experience. Needless to say, those managers had too little time to implement their vision at the clubs based upon the financial resources available to them.

Finally, confounding of team resources, reputation, and management capability can’t be underestimated. A manager with a mediocre or un-established reputation who is given the aura and the budget of a Chelsea or Arsenal should certainly be able to attract better talent than a similar manager at a less storied and financially resourceful club. This can especially come into play when measuring consistency of performance versus the model, where more established clubs can be expected to have less of a boom/bust cycle in spending and provide greater stability in personnel and performance. Looking at how performance varies with MSq£ attempts to minimize the effects of these related factors, but it can’t eliminate them.

With the aforementioned caveats in mind, the table below summarizes the 40 managers’ performance versus the regression model. Just like the similar table of 33 teams, the table below has been sorted by over/under performance first, then by standard deviation of the manager’s residuals to the regression model, and then by the manager’s average residual to the regression model. The table exhibits results that are far more skewed to the “over performance” and “push” categories than the club-based study, which is likely a result of the confounding factors discussed above. Astute readers will compare this table to those found in chapter two of Pay As You Play, which uses the £XI metric for its comparisons (click table to enlarge).

First things first: a discussion of Evans, Houllier, and Benitez. Liverpool fans are sure to jump on the presence of their last three managers being in the top five and state, “It sure didn’t feel like they were over performing!” It must be kept in mind that this table is sorted by the consistency of performance once over/under performance is determined. Outside of the three-year stints of Chris Coleman and John Gregory, the three previous Liverpool managers provided the most consistent performance of any over performing manager in the history of the Premier League. They also represented some of the most consistent MSq£’s across multiple managers for a single club. Evans certainly should have performed a bit better given that he always had a squad cost that was equal to or better the champions each season, although his utilization rate was 90% or below versus the maximum utilization each season. Houllier and Benitez, for all their faults, performed as expected given that they were always outspent by at least two teams each season. During Houllier’s term, it was Arsenal and Manchester United who constantly won the championship by having MSq£’s of 2.0 or greater. By the time Rafael Benitez took over, Manchester United and Chelsea had begun trading the championship back and forth with MSq£’s that had gone well over 2.5 and 3.0, respectively. By the end of Benitez’s term he was being outspent by four teams, which only compounded the issues associated with low club morale and an uncertain financial future.

The two top managers on the list provide perhaps an instruction in setting realistic expectations of management.

Chris Coleman’s three full years at Fulham showed him prevailing against the financial odds. Coleman began his tenure in 2003-04 season with a squad that cost £76.8M (MSq£ of 0.77) and finished 9th. The team’s immediate drop in value in the next season to £48.9M (MSq£ of 0.53) via the departure of Steve Marlet is a bit misleading, given Marlet’s minimal contribution of one match in 2003-2004 before he was transferred to Olympique Marseille. While Fulham subsequently sold key players like Edwin van der Sar, Louis Saha, and Luis Boa Morte for tidy profits, the reinvestment in players did not translate into improved performance. Despite exceeding expectations and avoiding relegation as every Fulham manager must do, as well as consistently outperforming the budget he was given, Coleman was replaced by Lawrie Sanchez in late 2007 as Fulham battled relegation again and finished in the 16th position indicative of their squad transfer cost.

John Gregory’s term at Aston Villa from the 1998/99 through the 2001/02 season is a story similar to Chris Coleman’s. Gregory may also prove to be one of Pay as You Play’s cautionary tales of smaller club success stories not translating to bigger club Premiership success. Gregory’s expenditures were much bigger than Chris Coleman’s at Fulham, with Gregory bouncing between an MSq£ of 1.06 and 1.14. This was good enough to suggest a mid-table finish of 10th each year, while Gregory exceeded this expectation by finishing sixth twice and eighth once (in his final full year). Indeed, this is spot on with Aston Villa’s historical average for both spend and table position during their eighteen years in the Premier League. Nonetheless, high expectations were set in 1998/99 when Villa were top of the table at the mid way point of the season only to finish sixth. Further finishes in this region of the table, and a backslide by the 2001/02 season, sealed Gregory’s fate with an ownership group and supporters who may have had unrealistic expectations for the club given their expenditures.

Further down the list, Roy Hodgson and Harry Redknapp provide interesting studies given the clubs they have managed this year.

Hodgson essentially got his first break at a big club in the Premier League via Liverpool after brief stints at Blackburn a decade ago and Fulham the last few years. His stint at Blackburn saw him finish sixth the one full season he was their manager, with Rovers getting relegated the next season in which he shared management responsibilities with Brian Kidd after Hodgson was sacked for a horrible start. Poor form was simply too much to take for a squad which cost £190M (MSq£ of 1.9). Hodgson’s two other seasons came with Fulham, where he parlayed a meager budget in 2008-09 (£51.3M for an MSq£ of 0.46) into sixth place and Europa League qualification. His second year at Fulham was much worse in league position (12th with a cost of £54.4M/MSq£ of 0.51), but a strong Europa League run balanced out this poor showing in the eyes of the press. Hodgson’s departure for Liverpool was a disaster, with the club sinking to 12th in the table before he was sacked for underperformance against everyone's expectations.

Harry Redknapp’s checkered career is certainly a more successful one. He took two clubs that were perennial doormats – West Ham United and Portsmouth – and made them perennial mid-table teams under his tenure. Redknapp’s performance versus the regression model certainly has benefited from timely departures from these clubs, with West Ham being relegated two seasons after his departure in 2001 and Portsmouth’s administration and relegation one year after his departure. He inherited a costly club with Tottenham in 2008 – £215.4M for an MSq£ of 1.94 – that was under performing in the relegation zone and guided them to an eighth place finish. His first full season with Tottenham saw him trim the squad cost and put his own stamp on the personnel for a total cost of £178.9M and an MSq£ of 1.68. Redknapp’s managerial skills guided Spurs to their best finish in the Premier League era and a Champions League berth. Tottenham is now seen as one of the new members of the expanded Big Six.

Worth a brief mention is Sam Allardyce, often considered one of the best managers at exceeding the expectation of his clubs’ meager budgets. Much of his poor variation is due to his first two seasons at Bolton when he performed as financially expected and barely dodged relegation, as well as his one full season at Newcastle United where he failed to meet the expectations set by the squad cost for only the second time in his career. Thus, it’s his massive success in his later years at Bolton and single full season at Blackburn that created such wide variability in residual values. Truly strange was his sacking at Blackburn this season. He grossly exceeded expectations based upon squad cost by over five positions in 2009/10, and was doing so again in 2010/11 when sacked. It is befuddling what Blackburn’s management team expects given their meager financial resources.

In the end, this further exemplifies why the MSq£ regression model is a valuable addition to the metrics discussed in Pay As You Play. Much of the discussion in Pay As You Play centered on the order, or relative position, of squad and on-pitch costs between the teams. This helps explain who’s spending more or less than each other and what expectations such an order entails, but it doesn’t explain how much more or less is being spent nor the effect of such gaps in spending. This is analogous to the gap between first and second in the table explaining order of finish, but the point gap is what helps explain the true difference in quality between the two teams. Similarly, increases in transfer spending, especially on the order of multiples, on average create greater separation (both nominally and distribution wise) between expected team finishes. To be more assured of a higher spot, a team must spend much more than its rival clubs. Otherwise, history as quantified via the regression equation teaches us that lower multiples of the league average give us a lower average finish and greater uncertainty of a finish via the prediction intervals.

Take a look at a specific example to understand this point. Liverpool’s current fifth highest squad transfer cost in the league (1.35 MSq) translates to a nominal predicted finish of 8.62. The maximum and minimum values for the 50% PI given Liverpool’s current MSq£ are 10.45 and 6.69. Thus, the statistical model captures the fact that historical variation of teams with similar transfer cost advantages have met expectations by finishing between 10th and 7th (when rounded). If Liverpool wants to be more assured of a higher final table position, they must spend more money on transfers. The reality is that Liverpool has been overachieving for years given their squad cost, both in terms of transfers and wages. With more teams spending a greater multiple of the league average than Liverpool, and as Liverpool slides further back towards the pack in transfer spending, they lose certainty in their likely final table position.

On the other hand the model only explains 70% of the variation we see. The other 30% can be accounted for in managerial mistakes, injuries, youth policies, and the like. One need look no further than Chelsea and their performance this season. Their transfer cost is still the highest in the league, but down from their historical highs. Looking at such a trend via the regression equation helps one understand what they’re seeing on the pitch – a thinner squad, populated by older players, trying to rebuild via a youth policy. The result is a less dominant Chelsea that appears to be challenging for a Champions League qualifying position instead of the Premier League championship. At Liverpool, Hodgson demonstrated a manager often has difficulty doing the opposite – grossly overachieve given the tactics one brings to the club given the players that he has available to him. Kenny Dalglish, with virtually the same team, has been able to extract much better form, and thus many more points, than Hodgson was able to during his tenure. These are the type of insights a regression analysis can provide beyond a traditional rank order analysis, but each is critical to understanding the total picture.

Conclusions

Through this two post series a method for evaluating a club and/or manager’s use of their resources has been developed, and it respects the implicit variability in results that are expected when analyzing squad transfer cost and table position. A differentiation has been made between the £XI metric used in Pay as You Play and the Sq£ metric preferred in this series of posts. Finally, a few projections have been made as to the financial resources required of Liverpool, or any team for that matter, to improve their chances of qualifying for Champions League.

At the end of the day, the use of the Sq£ metric in analyzing the correlation between club expenditures and finish position is really about setting realistic expectations. The first is that one must not kid themselves that the Premier League will be dominated by the financially well off, of which there is an increasing number. The second is that lower level clubs should not kid themselves as to the superior performance their managers may be leveraging given the meager financial resources they are afforded. Spending the money on transfers is only an enabler, not a guarantee, of success. Translating those expenditures into playing time and on-pitch performance is the true guarantee of success, and is often found in the actual managerial skills of the man entrusted with the overall performance of the team. For that there may be no financial measure.

Final Note: None of this work would be possible without the outstanding Transfer Price Index database assembled by Paul Tomkins and Graeme Riley, as well as Paul's generosity in sharing it with me. If you've liked this series of posts, I highly encourage you pick up a copy of Paul and Graeme's Pay As You Play (available in both paperback and Kindle formats). Not only will it continue to enlighten you as to the business aspects of the Premier League, but all proceeds go to charity. Paul and Graeme also continue to extend the book's content at Paul's website, The Tomkins Times, and at the book's website, The Transfer Price Index. Thank you to Paul and Graeme for all of their help and generosity!

No comments:

Post a Comment